Back pain

| Back pain | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

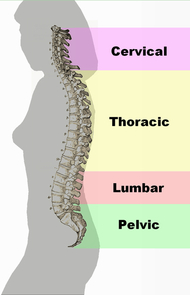

Different regions (curvatures) of the vertebral column |

|

| ICD-10 | M54. |

| ICD-9 | 724.5 |

| DiseasesDB | 15544 |

| MeSH | D001416 |

Back pain (also known "dorsalgia") is pain felt in the back that usually originates from the muscles, nerves, bones, joints or other structures in the spine.

The pain can often be divided into neck pain, upper back pain, lower back pain or tailbone pain. It may have a sudden onset or can be a chronic pain; it can be constant or intermittent, stay in one place or radiate to other areas. It may be a dull ache, or a sharp or piercing or burning sensation. The pain may be radiate into the arm and hand), in the upper back, or in the low back, (and might radiate into the leg or foot), and may include symptoms other than pain, such as weakness, numbness or tingling.

Back pain is one of humanity's most frequent complaints. In the U.S., acute low back pain (also called lumbago) is the fifth most common reason for physician visits. About nine out of ten adults experience back pain at some point in their life, and five out of ten working adults have back pain every year.[1]

The spine is a complex interconnecting network of nerves, joints, muscles, tendons and ligaments, and all are capable of producing pain. Large nerves that originate in the spine and go to the legs and arms can make pain radiate to the extremities.

Contents |

Classification

Back pain can be divided anatomically: neck pain, upper back pain, lower back pain or tailbone pain.

By its duration: acute (less than 4 weeks), subacute (4 – 12 weeks), chronic (greater than 12 weeks).

By its cause: MSK, infectious, cancer, etc.

Back pain is classified according to etiology in mechanical or nonspecific back pain and secondary back pain. Approximately 98% of back pain patients are diagnosed with nonspecific acute back pain which has no serious underlying pathology. However, secondary back pain which is caused by an underlying condition accounts for nearly 2% of the cases. Underlying pathology in these cases may include metastatic cancer, spinal osteomyelitis and epidural abscess which account for 1% of the patients. Also, herniated disc is the most common neurologic impairment which is associated with this condition, from which 95% of disc herniations occur at the lowest two lumbar intervertebral level. [2]

Associated conditions

Back pain can be a sign of a serious medical problem, although this is not most frequently the underlying cause:

- Typical warning signs of a potentially life-threatening problem are bowel and/or bladder incontinence or progressive weakness in the legs.

- Severe back pain (such as pain that is bad enough to interrupt sleep) that occurs with other signs of severe illness (e.g. fever, unexplained weight loss) may also indicate a serious underlying medical condition.

- Back pain that occurs after a trauma, such as a car accident or fall may indicate a bone fracture or other injury.

- Back pain in individuals with medical conditions that put them at high risk for a spinal fracture, such as osteoporosis or multiple myeloma, also warrants prompt medical attention.

- Back pain in individuals with a history of cancer (especially cancers known to spread to the spine like breast, lung and prostate cancer) should be evaluated to rule out metastatic disease of the spine.

Back pain does not usually require immediate medical intervention. The vast majority of episodes of back pain are self-limiting and non-progressive. Most back pain syndromes are due to inflammation, especially in the acute phase, which typically lasts for two weeks to three months.

A few observational studies suggest that two conditions to which back pain is often attributed, lumbar disc herniation and degenerative disc disease may not be more prevalent among those in pain than among the general population, and that the mechanisms by which these conditions might cause pain are not known.[3][4][5][6] Other studies suggest that for as many as 85% of cases, no physiological cause can be shown.[7][8]

A few studies suggest that psychosocial factors such as on-the-job stress and dysfunctional family relationships may correlate more closely with back pain than structural abnormalities revealed in x-rays and other medical imaging scans.[9][10][11][12]

Differential diagnosis

There are several potential sources and causes of back pain.[13] However, the diagnosis of specific tissues of the spine as the cause of pain presents problems. This is because symptoms arising from different spinal tissues can feel very similar and is difficult to differentiate without the use of invasive diagnostic intervention procedures, such as local anesthetic blocks.

One potential source of back pain is skeletal muscle of the back. Potential causes of pain in muscle tissue include muscle strains (pulled muscles), muscle spasm, and muscle imbalances. However, imaging studies do not support the notion of muscle tissue damage in many back pain cases, and the neurophysiology of muscle spasm and muscle imbalances are not well understood.

Another potential source of low back pain is the synovial joints of the spine (e.g. zygapophysial joints/facet joints. These have been identified as the primary source of the pain in approximately one third of people with chronic low back pain, and in most people with neck pain following whiplash.[13] However, the cause of zygapophysial joint pain is not fully understood. Capsule tissue damage has been proposed in people with neck pain following whiplash. In people with spinal pain stemming from zygapophysial joints, one theory is that intra-articular tissue such as invaginations of their synovial membranes and fibro-adipose meniscoids (that usually act as a cushion to help the bones move over each other smoothly) may become displaced, pinched or trapped, and consequently give rise to nociception (pain).

There are several common other potential sources and causes of back pain: these include spinal disc herniation and degenerative disc disease or isthmic spondylolisthesis, osteoarthritis (degenerative joint disease) and spinal stenosis, trauma, cancer, infection, fractures, and inflammatory disease.[14]

Radicular pain (sciatica) is distinguished from 'non-specific' back pain, and may be diagnosed without invasive diagnostic tests.

New attention has been focused on non-discogenic back pain, where patients have normal or near-normal MRI and CT scans. One of the newer investigations looks into the role of the dorsal ramus in patients that have no radiographic abnormalities. See Posterior Rami Syndrome.

Management

The management goals when treating back pain are to achieve maximal reduction in pain intensity as rapidly as possible; to restore the individual's ability to function in everyday activities; to help the patient cope with residual pain; to assess for side-effects of therapy; and to facilitate the patient's passage through the legal and socioeconomic impediments to recovery. For many, the goal is to keep the pain to a manageable level to progress with rehabilitation, which then can lead to long term pain relief. Also, for some people the goal is to use non-surgical therapies to manage the pain and avoid major surgery, while for others surgery may be the quickest way to feel better.

Not all treatments work for all conditions or for all individuals with the same condition, and many find that they need to try several treatment options to determine what works best for them. The present stage of the condition (acute or chronic) is also a determining factor in the choice of treatment. Only a minority of back pain patients (most estimates are 1% - 10%) require surgery.

Short-term relief

- Heat therapy is useful for back spasms or other conditions. A meta-analysis of studies by the Cochrane Collaboration concluded that heat therapy can reduce symptoms of acute and sub-acute low-back pain.[15] Some patients find that moist heat works best (e.g. a hot bath or whirlpool) or continuous low-level heat (e.g. a heat wrap that stays warm for 4 to 6 hours). Cold compression therapy (e.g. ice or cold pack application) may be effective at relieving back pain in some cases.

- Use of medications, such as muscle relaxants,[16] opioids, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs/NSAIAs)[17] or paracetamol (acetaminophen). A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials by the Cochrane Collaboration found that there is insufficient clinical trials to determine if injection therapy, usually with corticosteroids, helps in cases of low back pain[18] A study of intramuscular corticosteroids found no benefit.[19]

- Massage therapy, especially from an experienced therapist, can provide short term relief.[20] Acupressure or pressure point massage may be more beneficial than classic (Swedish) massage.[21]

Depending on the particular cause of the condition, posture training courses and physical exercises might help with relieving the pain. Specialists often recommend their patients to try out different exercises that would strengthen the back's musculature and bones. [22] Also, it has been claimed that vitamins such as vitamin D and B12 or magnesium, creams such as capsaicin cream, or plants such as willow bark or music therapy may help in relieving back pain, although it has not been proven to what extent they can be effective.

Conservative treatments

- Exercises can be an effective approach to reducing pain, but should be done under supervision of a licensed health professional. Generally, some form of consistent stretching and exercise is believed to be an essential component of most back treatment programs. However, one study found that exercise is also effective for chronic back pain, but not for acute pain.[23] Another study found that back-mobilizing exercises in acute settings are less effective than continuation of ordinary activities as tolerated.[24]

- Physical therapy consisting of manipulation and exercise, including stretching and strengthening (with specific focus on the muscles which support the spine). 'Back schools'[25] have shown benefit in occupational settings. The Schroth method, a specialized physical exercise therapy for scoliosis, kyphosis, spondylolisthesis, and related spinal disorders, has been shown to reduce severity and frequency of back pain in adults with scoliosis.[26]

- A randomized control trial, published in the British Medical Journal, found that the The Alexander Technique provided long term benefits for patients with chronic back pain.[27] A subsequent review concluded that 'a series of six lessons in Alexander technique combined with an exercise prescription seems the most effective and cost effective option for the treatment of back pain in primary care'[20].

- Studies of manipulation suggest that this approach has a benefit similar to other therapies and superior to placebo.[28][29]

- Acupuncture has some proven benefit for back pain;[30] however, a recent randomized controlled trial suggested insignificant difference between real and sham acupuncture.[31]

- Education, and attitude adjustment to focus on psychological or emotional causes[32] - respondent-cognitive therapy and progressive relaxation therapy can reduce chronic pain.[33]

Surgery

Surgery may sometimes be appropriate for patients with:

- Lumbar disc herniation or degenerative disc disease

- Spinal stenosis from lumbar disc herniation, degenerative joint disease, or spondylolisthesis

- Scoliosis

- Compression fracture

Minimally invasive surgical procedures are often a solution for many symptoms and causes of back pain. These types of procedures offer many benefits over traditional spine surgery, such as more accurate diagnoses and shorter recovery times.[34]

Surgery is usually the last resort in the treatment of back pain. It is normally recommended only if all other treatment options have been tried or if the situation is an emergency. A 2009 systematic review of back surgery studies found that, for certain diagnoses, surgery is moderately better than other common treatments, but the benefits of surgery often decline in the long term.[35]

There are different types of surgical procedures that are used in treating various conditions causing back pain. All of them can be classified into nerve decompression, fusion of body segments and deformity correction surgeries. [36] The first type of surgery is primarily performed in older patients who suffer from conditions causing nerve irritation or nerve damage. Fusion of bony segments is also referred to as a spinal fusion, and it is a procedure used to fuse together two or more bony fragments with the help of metalwork. The latter type of surgery is normally performed to correct congenital deformities or those that were caused by a traumatic fracture. In some cases, correction of deformities involves removing bony fragments or providing stability provision for the spine.

The main procedures used in back pain surgery are discetomies, spinal fusions, laminectomies, removal of tumors, and vertebroplasties.

A discetomy is performed when the intervertebral disc have herniated or tore. It involves removing the protruding disc, either a portion of it or all of it, that is placing pressure on the nerve root. [37] The disc material which is putting pressure on the nerve is removed through a small incision that is made over that particular disc. This is one of the most popular types of back surgeries and which also has a high rate of success. The recovery period after this procedure does not last longer than 6 weeks. The type of procedure in which the bony fragments are removed through an endoscope is called percutaneous disc removal.

Microdiscetomies may be performed as a variation of standard discetomies in which a magnifier is used to provide the advantage of a smaller incision, thus a shorter recovery process.

Spinal fusions are performed in cases in which the patient has had the entire disc removed or when another condition has caused the vertebrae to become unstable. The procedure consists in uniting two or more vertebrae by using bone grafts and metalwork to provide more strength for the healing bone. Recovery after spinal fusion may take up to one year, depending greatly on the age of the patient, the reason why surgery has been performed and how many bony segments needed to be fused.

In cases of spinal stenosis or disc herniation, laminectomies can be performed to relieve the pressure on the nerves. During such a procedure, the surgeon enlarges the spinal canal by removing or trimming away excessive lamina which will provide more space for the nerves. The severity of the condition as well as the general health status of the patient are key factors in establishing the recovery time, which may be range from 8 weeks to 6 months.

Back surgery can be performed to prevent the growth of benign and malignant tumors. In the first case, surgery has the goal of relieving the pressure from the nerves which is caused by a benign growth, whereas in the latter the procedure is aimed to prevent the spread of cancer to other areas of the body. Recovery depends on the type of tumor that is being removed, the health status of the patient and the size of the tumor.[38]

Of doubtful benefit

- Cold compression therapy is advocated for a strained back or chronic back pain and is postulated to reduce pain and inflammation, especially after strenuous exercise such as golf, gardening, or lifting. However, a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials by the Cochrane Collaboration concluded "The evidence for the application of cold treatment to low-back pain is even more limited, with only three poor quality studies located. No conclusions can be drawn about the use of cold for low-back pain"[15]

- Bed rest is rarely recommended as it can exacerbate symptoms,[39] and when necessary is usually limited to one or two days. Prolonged bed rest or inactivity is actually counterproductive, as the resulting stiffness leads to more pain.

- Electrotherapy, such as a transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) has been proposed. Two randomized controlled trials found conflicting results.[40][41] This has led the Cochrane Collaboration to conclude that there is inconsistent evidence to support use of TENS.[42] In addition, spinal cord stimulation, where an electrical device is used to interrupt the pain signals being sent to the brain and has been studied for various underlying causes of back pain.

- Inversion therapy is useful for temporary back relief due to the traction method or spreading of the back vertebres through (in this case) gravity. The patient hangs in an upside down position for a period of time from ankles or knees until this separation occurs. The effect can be achieved without a complete vertical hang ( 90 degree) and noticeable benefits can be observed at angles as low as 10 to 45 degrees.

- Ultrasound has been shown not to be beneficial and has fallen out of favor.[43]

Pregnancy

About 50% of women experience low back pain during pregnancy.[44] Back pain in pregnancy may be severe enough to cause significant pain and disability and pre-dispose patients to back pain in a following pregnancy. No significant increased risk of back pain with pregnancy has been found with respect to maternal weight gain, exercise, work satisfaction, or pregnancy outcome factors such as birth weight, birth length, and Apgar scores.

Biomechanical factors of pregnancy that are shown to be associated with low back pain of pregnancy include abdominal sagittal and transverse diameter and the depth of lumbar lordosis. Typical factors aggravating the back pain of pregnancy include standing, sitting, forward bending, lifting, and walking. Back pain in pregnancy may also be characterized by pain radiating into the thigh and buttocks, night-time pain severe enough to wake the patient, pain that is increased during the night-time, or pain that is increased during the day-time. The avoidance of high impact, weight-bearing activities and especially those that asymmetrically load the involved structures such as: extensive twisting with lifting, single-leg stance postures, stair climbing, and repetitive motions at or near the end-ranges of back or hip motion can easen the pain. Direct bending to the ground without bending the knee causes severe impact on the lower back in pregnancy and in normal individuals, which leads to strain, especially in the lumbo-saccral region that in turn strains the multifidus.

Economics

Back pain is regularly cited by national governments as having a major impact on productivity, through loss of workers on sick leave. Some national governments, notably Australia and the United Kingdom, have launched campaigns of public health awareness to help combat the problem, for example the Health and Safety Executive's Better Backs campaign. In the United States lower back pain’s economic impact reveals that it is the number one reason for individuals under the age of 45 to limit their activity, second highest complaint seen in physician’s offices, fifth most common requirement for hospitalization, and the third leading cause for surgery.

Research

- Vertebroplasty involves the percutaneous injection of surgical cement into vertebral bodies that have collapsed due to compression fractures has been found to be ineffective in the treatment of compression fractures of the spine.

- The use of specific biologic inhibitors of the inflammatory cytokine tumor necrosis factor-alpha may result in rapid relief of disc-related back pain. [45]

Clinical trials

There are many clinical trials sponsored both by industry and the National Institutes of Health. Clinical trials sponsored by the National Institutes of Health related to back pain can be viewed at NIH Clinical Back Pain Trials.

Pain is subjective and is impossible to test objectively. There are no clinical tests that can be objectively verified. Clinical test utilize the patient's report o pain severity on a scale of 1 to 10. Sometimes and particularly with children a series of emoticons are presented to the patient and the subject is asked to point to an emoticon. Even though some clinical trials succeed in getting regulatory approval for products this is not a proof that this therapy is more effective or even has a benefit. All the tests rely on the patient's perception. The doctor can not verify whether 5 is a more appropriate score than 1 or 10 nor determine if one patient's 5 is comparable to another patient's rating of 5.

A 2008 randomized controlled trial found marked improvement in addressing back pain with The Alexander Technique. Exercise and a combination of 6 lessons of AT reduced back pain 72% as much as 24 AT lessons. Those receiving 24 lessons had 18 fewer days of back pain than the control median of 21 days.[27]

References

- ↑ A.T. Patel, A.A. Ogle. "Diagnosis and Management of Acute Low Back Pain". American Academy of Family Physicians. Retrieved March 12, 2007.

- ↑ "Back Pain". http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/457101_3. Retrieved June 18, 2010.

- ↑ Borenstein DG, O'Mara JW, Boden SD, et al. (2001). "The value of magnetic resonance imaging of the lumbar spine to predict low-back pain in asymptomatic subjects : a seven-year follow-up study". The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume 83-A (9): 1306–11. PMID 11568190.

- ↑ Savage RA, Whitehouse GH, Roberts N (1997). "The relationship between the magnetic resonance imaging appearance of the lumbar spine and low back pain, age and occupation in males". European spine journal : official publication of the European Spine Society, the European Spinal Deformity Society, and the European Section of the Cervical Spine Research Society 6 (2): 106–14. PMID 9209878.

- ↑ Jensen MC, Brant-Zawadzki MN, Obuchowski N, Modic MT, Malkasian D, Ross JS (1994). "Magnetic resonance imaging of the lumbar spine in people without back pain". N. Engl. J. Med. 331 (2): 69–73. doi:10.1056/NEJM199407143310201. PMID 8208267.

- ↑ Kleinstück F, Dvorak J, Mannion AF (2006). "Are "structural abnormalities" on magnetic resonance imaging a contraindication to the successful conservative treatment of chronic nonspecific low back pain?". Spine 31 (19): 2250–7. doi:10.1097/01.brs.0000232802.95773.89. PMID 16946663.

- ↑ White AA, Gordon SL (1982). "Synopsis: workshop on idiopathic low-back pain". Spine 7 (2): 141–9. doi:10.1097/00007632-198203000-00009. PMID 6211779.

- ↑ van den Bosch MA, Hollingworth W, Kinmonth AL, Dixon AK (2004). "Evidence against the use of lumbar spine radiography for low back pain". Clinical radiology 59 (1): 69–76. doi:10.1016/j.crad.2003.08.012. PMID 14697378.

- ↑ Burton AK, Tillotson KM, Main CJ, Hollis S (1995). "Psychosocial predictors of outcome in acute and subchronic low back trouble". Spine 20 (6): 722–8. doi:10.1097/00007632-199503150-00014. PMID 7604349.

- ↑ Carragee EJ, Alamin TF, Miller JL, Carragee JM (2005). "Discographic, MRI and psychosocial determinants of low back pain disability and remission: a prospective study in subjects with benign persistent back pain". The spine journal : official journal of the North American Spine Society 5 (1): 24–35. doi:10.1016/j.spinee.2004.05.250. PMID 15653082.

- ↑ Hurwitz EL, Morgenstern H, Yu F (2003). "Cross-sectional and longitudinal associations of low-back pain and related disability with psychological distress among patients enrolled in the UCLA Low-Back Pain Study". Journal of clinical epidemiology 56 (5): 463–71. doi:10.1016/S0895-4356(03)00010-6. PMID 12812821.

- ↑ Dionne CE (2005). "Psychological distress confirmed as predictor of long-term back-related functional limitations in primary care settings". Journal of clinical epidemiology 58 (7): 714–8. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.12.005. PMID 15939223.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Bogduk N | Clinical anatomy of the lumbar spine and sacrum, 4th edn. | Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone | 2005

- ↑ "Back Pain Information Page: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS)". Ninds.nih.gov. 2010-05-19. http://www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/backpain/backpain.htm. Retrieved 2010-06-02.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 French S, Cameron M, Walker B, Reggars J, Esterman A (2006). "A Cochrane review of superficial heat or cold for low back pain.". Spine 31 (9): 998–1006. doi:10.1097/01.brs.0000214881.10814.64. PMID 16641776.

- ↑ van Tulder M, Touray T, Furlan A, Solway S, Bouter L (2003). "Muscle relaxants for non-specific low back pain.". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2): CD004252. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004252. PMID 12804507.

- ↑ van Tulder M, Scholten R, Koes B, Deyo R (2000). "Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for low back pain.". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2): CD000396. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000396. PMID 10796356.

- ↑ Nelemans P, de Bie R, de Vet H, Sturmans F (1999). "Injection therapy for subacute and chronic benign low back pain". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2): CD001824. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001824. PMID 10796449.

- ↑ Friedman B, Holden L, Esses D, Bijur P, Choi H, Solorzano C, Paternoster J, Gallagher E (2006). "Parenteral corticosteroids for Emergency Department patients with non-radicular low back pain". J Emerg Med 31 (4): 365–70. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2005.09.023. PMID 17046475.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Sandra Hollinghurst et al.,Randomised controlled trial of Alexander technique lessons, exercise, and massage (ATEAM) for chronic and recurrent back pain: economic evaluation, British Medical Journal, 11 December 2008.

- ↑ Furlan A, Brosseau L, Imamura M, Irvin E (2002). "Massage for low back pain.". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2): CD001929. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001929. PMID 12076429.

- ↑ "Back Pain Exercises Routine Benefits". http://severebackpain.us/exercises.php. Retrieved June 18, 2010.

- ↑ Hayden J, van Tulder M, Malmivaara A, Koes B (2005). "Exercise therapy for treatment of non-specific low back pain.". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (3): CD000335. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000335.pub2. PMID 16034851.

- ↑ Malmivaara A, Häkkinen U, Aro T, Heinrichs M, Koskenniemi L, Kuosma E, Lappi S, Paloheimo R, Servo C, Vaaranen V (1995). "The treatment of acute low back pain--bed rest, exercises, or ordinary activity?". N Engl J Med 332 (6): 351–5. doi:10.1056/NEJM199502093320602. PMID 7823996.

- ↑ Heymans M, van Tulder M, Esmail R, Bombardier C, Koes B (2004). "Back schools for non-specific low-back pain.". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4): CD000261. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000261.pub2. PMID 15494995.

- ↑ Weiss HR, Scoliosis-related pain in adults: Treatment influences. Eur J Phys Med Rehabil 1993; 3(3):91-94.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Paul Little et al.,Randomised controlled trial of Alexander technique (AT) lessons, exercise, and massage (ATEAM) for chronic and recurrent back pain, British Medical Journal, August 19, 2008.

- ↑ Assendelft W, Morton S, Yu E, Suttorp M, Shekelle P (2004). "Spinal manipulative therapy for low back pain.". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1): CD000447. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000447.pub2. PMID 14973958.

- ↑ Cherkin D, Sherman K, Deyo R, Shekelle P (2003). "A review of the evidence for the effectiveness, safety, and cost of acupuncture, massage therapy, and spinal manipulation for back pain.". Ann Intern Med 138 (11): 898–906. PMID 12779300.

- ↑ "Acupuncture and dry-needling for low back pain". Cochrane.org. 2003-06-02. http://www.cochrane.org/reviews/en/ab001351.html. Retrieved 2010-06-02.

- ↑ "Interventions - Low back pain (chronic) - Musculoskeletal disorders - Clinical Evidence". Clinicalevidence.bmj.com. http://clinicalevidence.bmj.com/ceweb/conditions/msd/1116/1116.jsp. Retrieved 2010-06-02.

- ↑ Sarno, John E. (1991). Healing Back Pain: The Mind-Body Connection. Warner Books. ISBN 0-446-39320-8.

- ↑ Ostelo R, van Tulder M, Vlaeyen J, Linton S, Morley S, Assendelft W (2005). "Behavioural treatment for chronic low-back pain.". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1): CD002014. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002014.pub2. PMID 15674889.

- ↑ "Compare Procedures - North American Spine". http://northamericanspine.com/compare-procedures. Retrieved 2010-03-31.

- ↑ http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19363455

- ↑ "Types of Surgery for Back Pain". http://www.backpainexpert.co.uk/TypesOfSurgeryAvailable.html. Retrieved June 18, 2010.

- ↑ "Surgery For Back Pain". http://www.ehealthmd.com/library/backpain/BAK_surgery.html. Retrieved June 18, 2010.

- ↑ "Types of Surgery for Back Pain". http://www.backpainexpert.co.uk/TypesOfSurgeryAvailable.html. Retrieved June 18, 2010.

- ↑ Hagen K, Hilde G, Jamtvedt G, Winnem M (2004). "Bed rest for acute low-back pain and sciatica.". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4): CD001254. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001254.pub2. PMID 15495012.

- ↑ Cheing GL, Hui-Chan CW (1999). "Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation: nonparallel antinociceptive effects on chronic clinical pain and acute experimental pain". Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation 80 (3): 305–12. doi:10.1016/S0003-9993(99)90142-9. PMID 10084439.

- ↑ Deyo RA, Walsh NE, Martin DC, Schoenfeld LS, Ramamurthy S (1990). "A controlled trial of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) and exercise for chronic low back pain". N. Engl. J. Med. 322 (23): 1627–34. PMID 2140432.

- ↑ Khadilkar A, Milne S, Brosseau L, et al. (2005). "Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) for chronic low-back pain". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (3): CD003008. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003008.pub2. PMID 16034883.

- ↑ A Review of Therapeutic Ultrasound: Effectiveness Studies, Valma J Robertson, Kerry G Baker, Physical Therapy . Volume 81 . Number 7 . July 2001

- ↑ Ostgaard HC, Andersson GBJ, Karlsson K. Prevalence of back pain in pregnancy. Spine 1991;16:549-52.

- ↑ Uceyler N, Sommer C. Cytokine-induced Pain: Basic Science and Clinical Implications. Reviews in Analgesia 2007;9(2):87-103.

External links

- Back and spine at the Open Directory Project

- Handout on Health: Back Pain at National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases

- Back pain, on Medline plus, a service of the National Library of Medicine

- American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons summary on back pain

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||